The Best Fluffy Pancakes recipe you will fall in love with. Full of tips and tricks to help you make the best pancakes.

Since the 1920s, The Three Stooges have been icons of American comedy, famed for their slapstick routines and Columbia short films that gained new life on television in the 1950s. Beyond their pie-throwing and pratfalls lies a trove of lesser-known stories—behind-the-scenes mishaps, cast changes, and curious quirks. Their journey, both hilarious and human, continues to fascinate fans across generations. Dive into these hidden tales and uncover the deeper, more personal layers of the trio who redefined comedy.

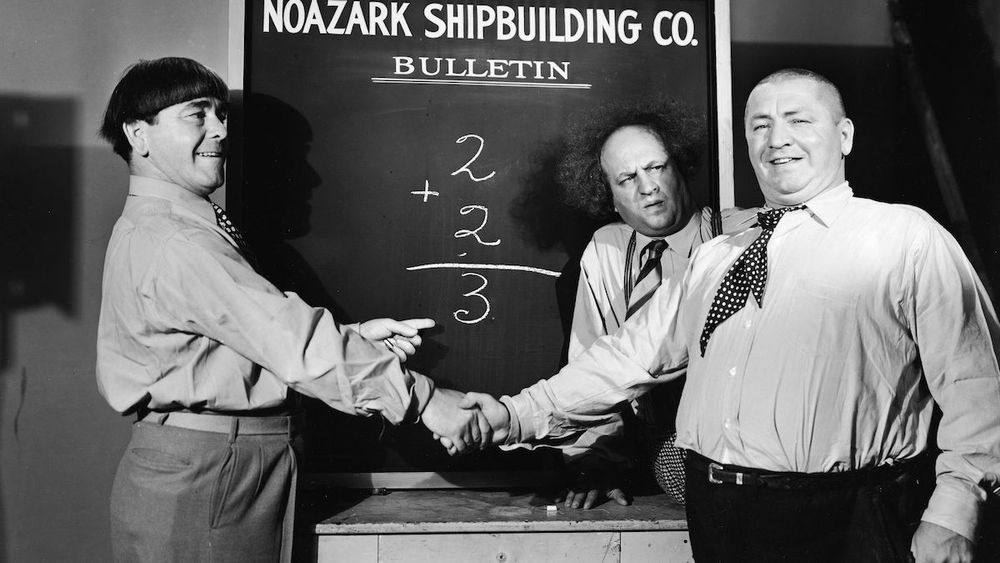

#1: The Origins of The Three Stooges

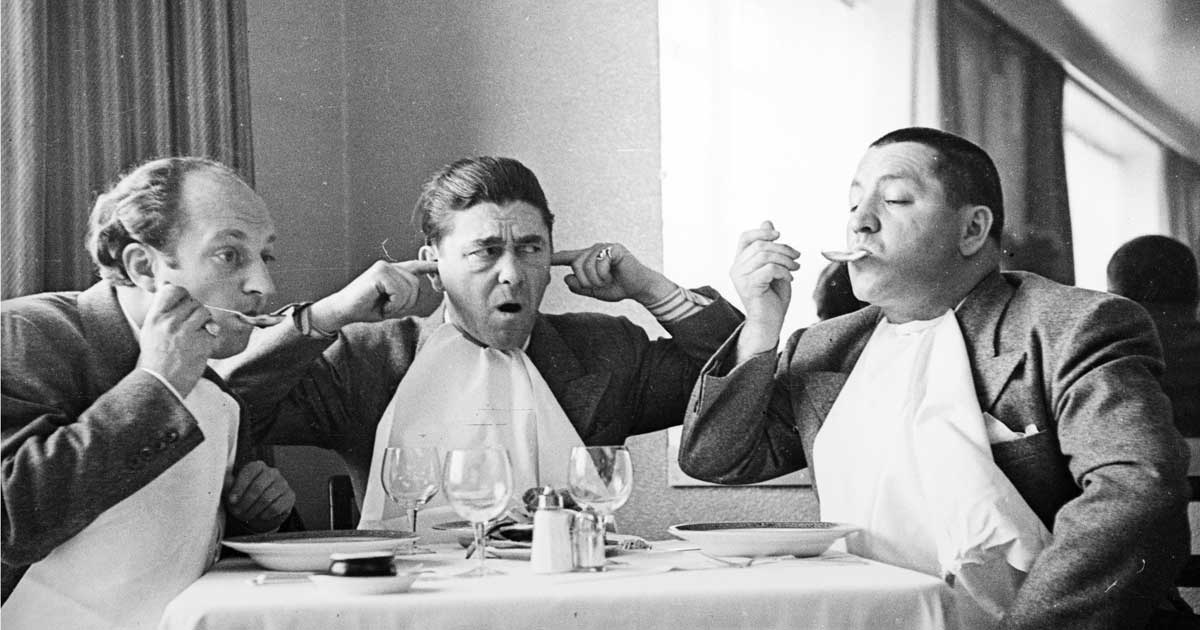

In the bustling vaudeville circuit of the 1920s, a comedic phenomenon began to take shape. It all started in 1922, when Moe Howard and his brother Shemp joined forces with vaudevillian Ted Healy. A violinist named Larry Fine later completed the trio, forming a quirky comedic unit that would evolve into The Three Stooges.

Their early performances relied on slapstick chaos and sharp timing, winning over live audiences with exaggerated antics. Though still under Healy’s shadow, their potential shimmered. These humble origins planted the seeds of a legacy, hinting at the whirlwind of mischief and laughter soon to follow.

#2: Shemp’s Departure

It was 1930, and the silver screen was calling. The Three Stooges, still bound to Ted Healy, were nearly catapulted into cinematic fame by a promising deal from 20th Century Fox. But the dream fizzled before it could ignite.

Healy, clinging tightly to control, asserted the Stooges were his hired men, not independent talent. His interference derailed the opportunity, and Fox rescinded their offer. The trio, brimming with potential, remained trapped in the wings. It was a stark reminder that success sometimes hinges not on talent or timing, but on the tangled web of egos, contracts, and misplaced loyalty.

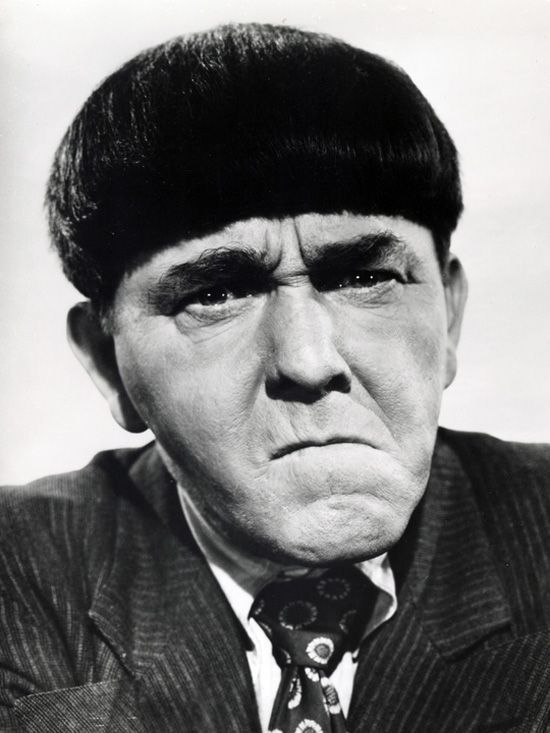

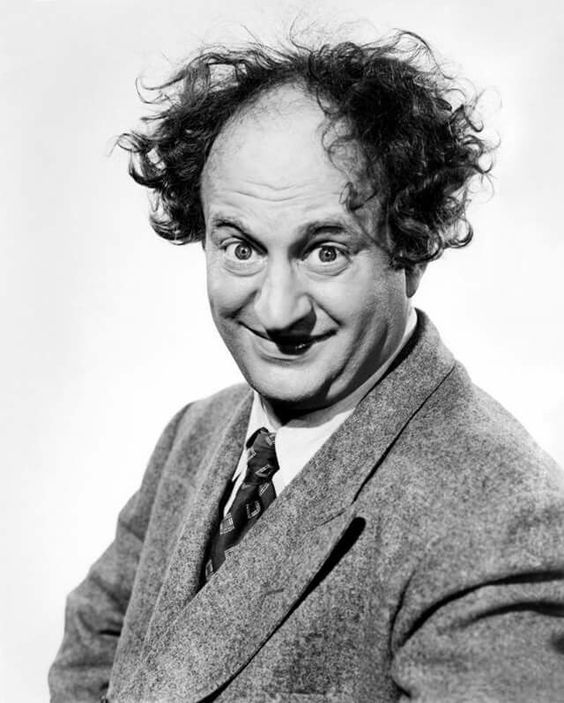

#3: The Difference Between Curly’s Public and Private Persona

Shemp Howard wasn’t one to suffer fools—or tyrants—quietly. As Ted Healy’s control tightened and tensions mounted, Shemp’s joy for performing waned. Moe may have been given managerial authority, but Healy’s domineering presence poisoned the atmosphere.

Tired of the toxic dynamics and yearning for creative space, Shemp bowed out and headed to Brooklyn. There, he pursued a solo career, immersing himself in comedy clubs and crafting a style that was more his own. While it seemed like a setback for the Stooges, Shemp’s departure opened new paths for all involved, reshaping the act in ways that would echo for decades.

ADVERTISEMENT

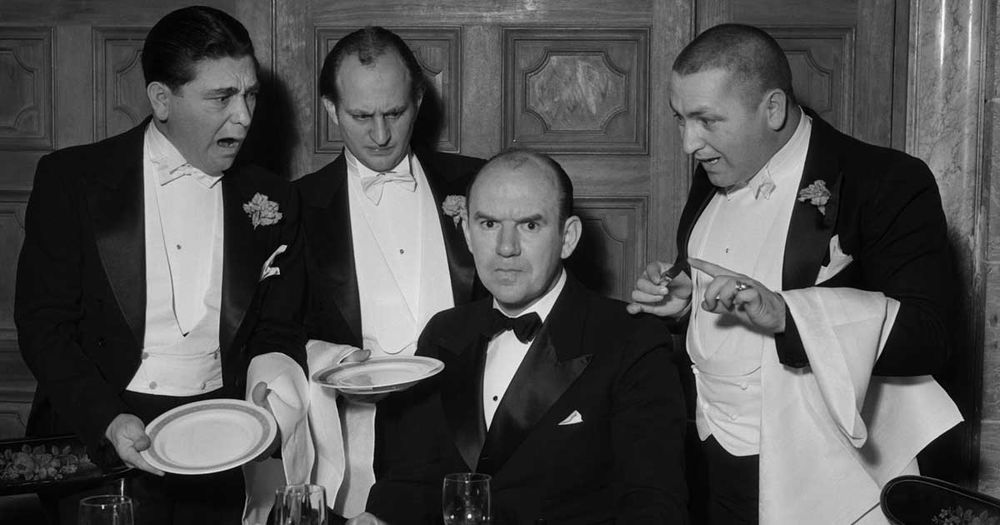

#4: The Mysterious End of Healy

Editorial content

Curly Howard was electric on screen—bounding, bellowing, and bursting with energy—but his offstage life was an unexpected contrast. Beneath the cartoonish persona lay a quiet soul who preferred solitude to spotlight and dogs to dialogue.

He rarely partied unless coaxed by drink, which increasingly became a crutch for his dual existence. Only among the other Stooges did that signature zest flicker naturally. Audiences saw the clown; few glimpsed the melancholic man within.

#5: Navigating the Dynamics of Stardom

Ted Healy, the tempestuous architect of the Stooges’ early fame, met an end as murky as his moods. In 1937, at just 41, he reportedly succumbed to a heart attack after celebrating his son’s birth in Los Angeles. But whispers quickly swirled—about bruises, barroom brawls, and a man with a notorious temper.

Was it alcohol-fueled violence? A fight turned fatal? Or simply nature’s cruel twist? No clear answer emerged, only a puzzle wrapped in shadows. His demise severed ties with his protégés forever, adding a final, chilling twist to the saga of a man who gave comedy chaos—at a cost.

#6: Financial Struggles of the Stooges

Columbia Pictures offered a lifeline—and a leash. Signed for 40 weeks to produce eight short films annually, the Stooges became a reliable moneymaker. Yet behind the curtain, the studio’s president, Harry Cohn, orchestrated a masterclass in manipulation.

He kept the trio in the dark about their popularity, using annual contract renewals to maintain a grip. The boys churned out hit after hit, unaware of how adored they were. Stardom glimmered just out of their reach. It wasn’t just about pies and pokes—it was about power, and how the business of laughter could also be an act of control.

#7: The Three Stooges’ Comedy

What began as a flub turned into folklore. Whenever Curly forgot his lines—an increasingly frequent occurrence—he’d spin in frantic circles, buying time with hilarity. It wasn’t scripted, rehearsed, or even planned. But it struck gold.

The absurdity of a grown man chasing his tail, complete with wild eyes and whoop-whoops, became a Stooge staple. Fans adored it. Directors demanded it. And suddenly, a moment of improvisation became immortalized. This is where comedy lives—in the cracks between perfection.

#8: Thrilling Feats and Mishaps

The pain was often real. Behind the buffoonery of pies and pratfalls, the Stooges flirted with danger—sometimes by accident, sometimes by choice. Larry once walked off set with a pen embedded in his skull from a misfired gag, and Curly returned from stitches to finish scenes as if injury were no big deal.

Yet, they knew their limits. During “Three Little Pigskins,” they balked at a football stampede stunt, leaving their doubles to suffer cracked ribs and broken bones. It was a rare rebellion—a moment when survival trumped slapstick.

#9: The Real Story Behind Curly’s Limp

Curly’s comic limp wasn’t pure invention. It was grounded in a childhood accident—an old scar from a gun mishap that left him with an awkward gait. Cleaning a rifle as a boy, he shot himself in the ankle, a moment of real-life pain that later found its way into screen routines.

What audiences saw as another absurd flourish was authentic. Of course, he exaggerated it—turning a wound into a bit, discomfort into delight. It became a hallmark of his performance, a reminder that the funniest details are often rooted in personal history.

#10: Economizing on The Three Stooges

Hollywood never gave The Three Stooges top billing, and their budgets reflected it. Recycled sets, borrowed wardrobes, reused props—this was the underbelly of their production process. Frugality wasn’t a choice; it was a necessity. But that didn’t stop them.

If anything, it sharpened their ingenuity. The trio turned constraints into creativity, crafting chaos from scraps. Their slapstick world looked grand, even if the backdrops had once hosted a drama or a western. In a town built on illusion, they stretched every dollar and every pie. Low budget didn’t mean low impact.

#11: The Dilemma of Curly’s Bald Transformation

Vanity and vulnerability collided when Curly took a razor to his thick hair and mustache. He wanted the part. Needed the laugh. So he shaved his head, knowing the comedic payoff but fearing what it might cost him personally. Women, he believed, would find him less attractive.

That fear, compounded by insecurity, led him down paths of excess—overeating, heavy drinking, and emotional spirals. The transformation wasn’t just physical; it reshaped his identity. Offstage, he mourned the man in the mirror. Onstage, he gave audiences a version of himself tailored for laughs.

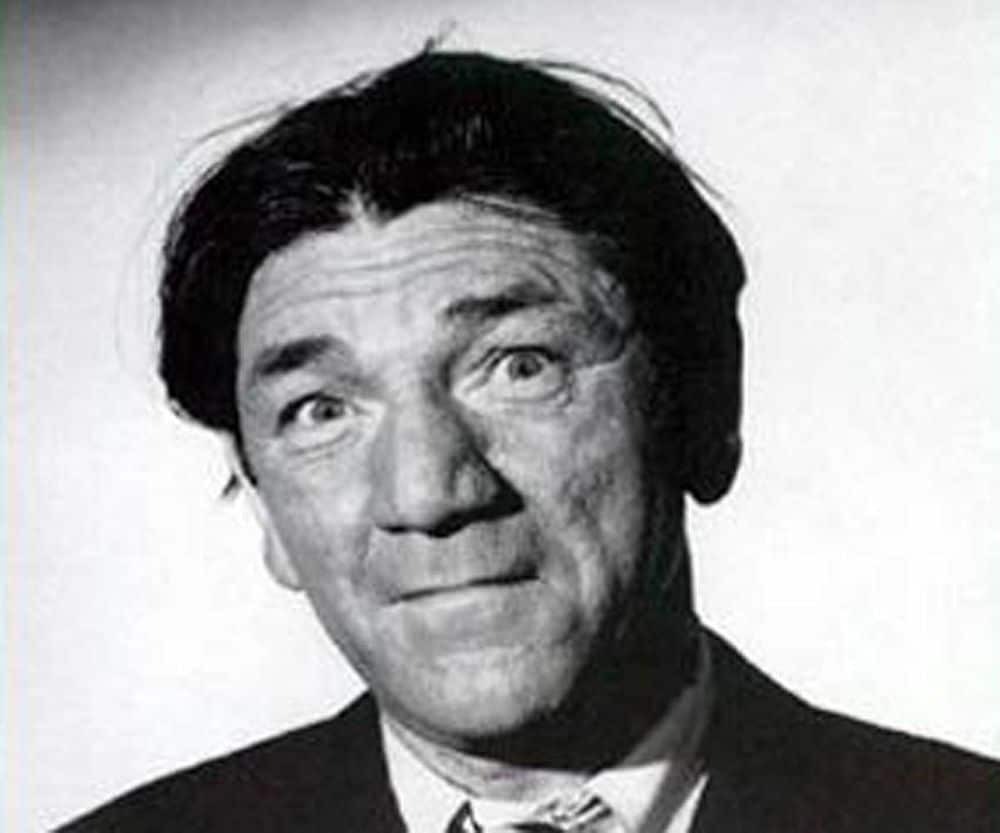

#12: The Iconic Bowl Cut of Moe

There’s irony in Moe Howard’s most defining feature: his signature bowl cut was a haircut born of rebellion. His mother longed for a daughter and let his curls grow wild. But Moe, tired of the teasing, hacked them off with scissors—an act of childhood defiance that became a lifelong trademark.

What began as a moment of self-assertion became visual shorthand for his tough-guy persona. With the blunt bangs and the stern eyes, Moe looked like the group’s enforcer because, in many ways, he was. Behind the slapstick, his hair told a story of grit, stubbornness, and self-made identity.

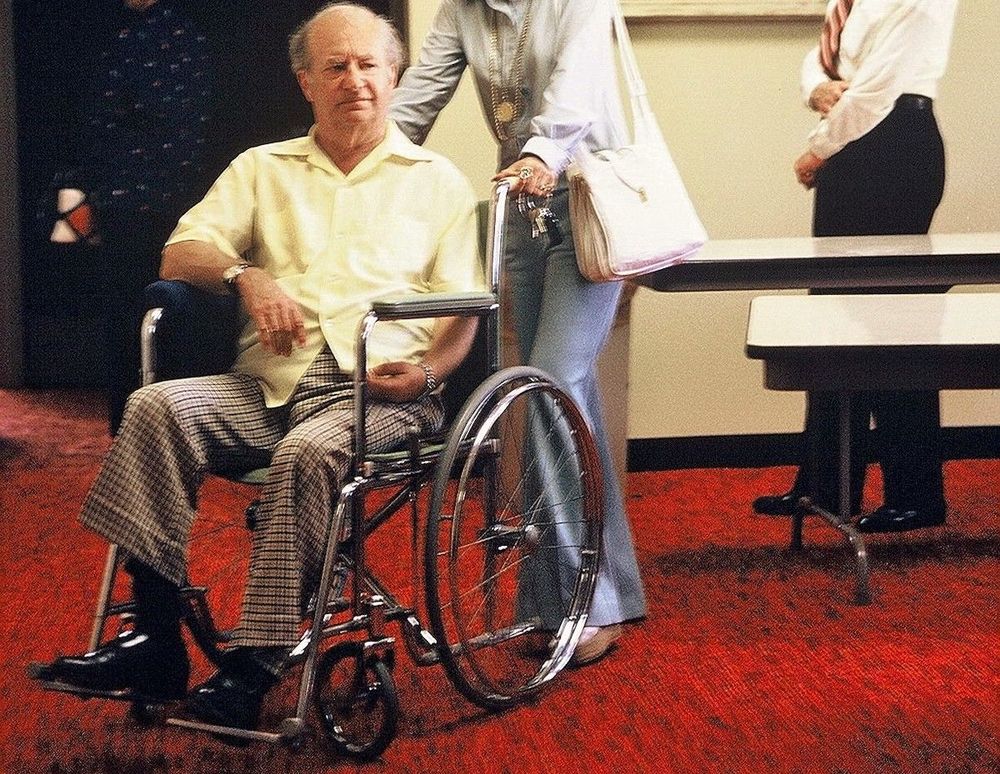

#13: The Decline of Curly’s Health

Curly, once beloved for his innocent humor, saw his health decline due to unhealthy habits. His condition worsened, leading to a career-stopping stroke in 1946, despite trying to maintain his film presence.

After a severe stroke halted his career, Curly made a brief comeback only to suffer another stroke. Confined to a wheelchair, he passed away as the youngest Stooge at 48, marking the end of an era.

#14: Shemp’s Comeback to the Three Stooges

After Curly suffered a stroke, Shemp rejoined the Stooges, with the industry pushing him to emulate Curly’s iconic role. Despite the audience’s preference for Curly, Shemp resisted copying his brother’s style, only to receive lukewarm reception for his efforts.

Shemp’s unexpected death during production led to the creative use of stand-ins and pre-existing footage to conclude his pending films seamlessly. This quick-fix solution maintained the illusion of his presence in completed works.

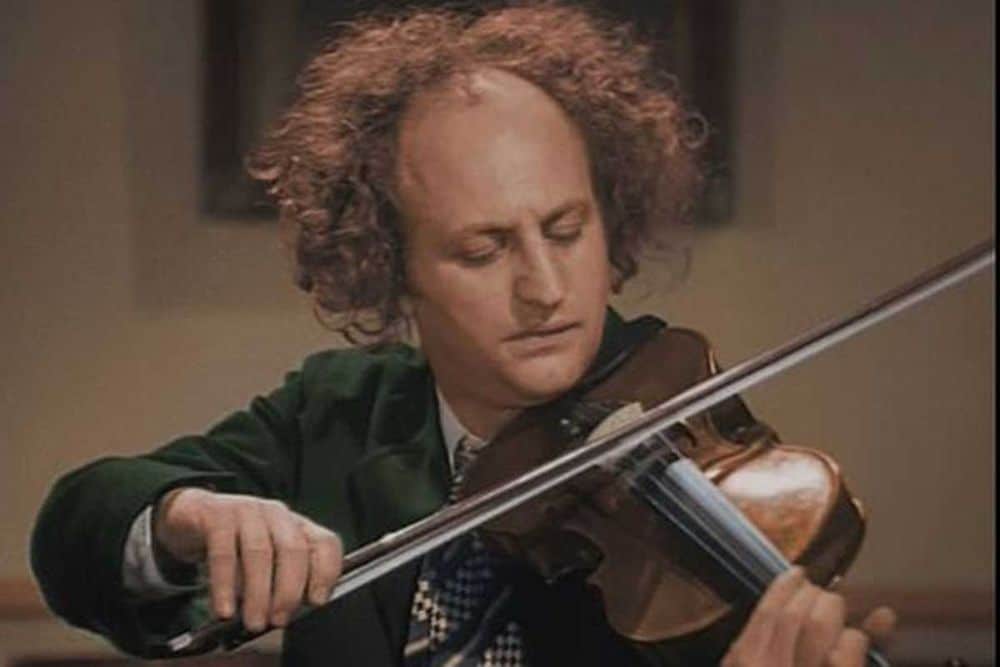

#15: Unusual Origin of a Musical Talent

Larry Fine’s violin skills weren’t the result of passion—they were penance. As a boy, he accidentally drank acid from his father’s jewelry workshop, severely damaging his arm. Doctors prescribed rehabilitation through movement, and thus, violin lessons began.

What started as therapy evolved into artistry. Larry developed a touch so sensitive it softened even his wildest onscreen moments. The violin became more than a prop—it was a lifeline. In many shorts, his bowing was genuine, his notes crisp. Comedy brought the slap, but music brought the soul.

#16: Moe’s Expertise in Pie-Throwing

You’d think anyone could throw a pie. Not Moe Howard. He believed there was a science to it. A pie too light would miss its mark. Too heavy, and it became a liability. Moe fine-tuned the art of cream-pie warfare with mathematical precision. He gauged velocity, angle, and trajectory.

His throws weren’t just funny—they were architectural. Studios limited the number of pies per shoot, so Moe made every splat count. His secret? A pie with just the right weight and filling—balanced, aerodynamic, inevitable. It was warfare wrapped in whipped cream, and Moe was its general, leading each messy assault with flair.

#17: The Dancing Spirit of Larry

By night, Larry Fine became someone else entirely. He wasn’t the shrieking Stooge or the fall guy. At Brooklyn’s Triangle Ballroom, he was fluid, elegant—a dancer in love with motion. He’d twirl through the night, soaked in music and moonlight, often arriving late to set, still buzzing from rhythm.

Even after a stroke left him wheelchair-bound, Larry’s spirit didn’t dim. He’d tap his fingers to imagined beats, eyes sparkling. Dancing wasn’t just a pastime—it was defiance. Against age, against paralysis, against expectations. When the laughter stopped and the lights dimmed, Larry still danced—if not on his feet, then somewhere deep inside.

#18: The Comedy of Slaps

A slap from Moe wasn’t always just smoke and mirrors. While sound effects typically added drama to those iconic smacks, there were moments—fleeting, but honest—when Moe connected. He believed the illusion should carry the sting, but now and then, he’d deliver a gentle pop for authenticity’s sake.

The audience never knew which was which. The key was commitment. Every swing, whether air or flesh, came from the same comedic conviction. The slaps became a language of their own—exaggerated punctuation in a chaotic sentence of pratfalls and pokes. In their world, pain was funny, and funny was unforgettable.

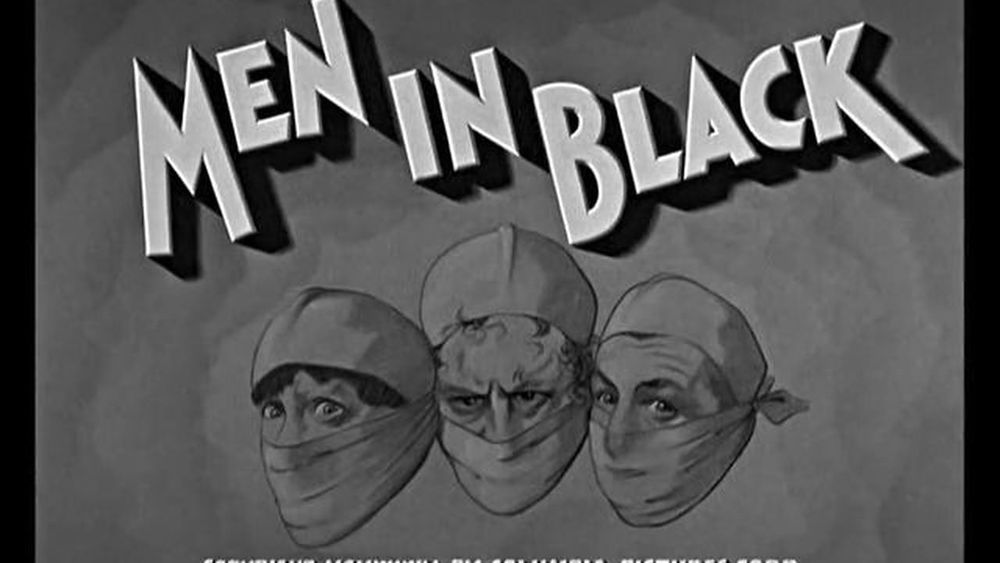

#19: Academy Award Recognition for the Stooges

In a rare twist of prestige meeting pie-in-the-face, The Three Stooges stunned critics by nabbing an Oscar nomination 1934 for Men in Black, a parody of hospital dramas. It was a seismic moment—comedy, often sidelined in favor of dramatic gravitas, had elbowed its way into Hollywood’s upper echelon.

The short film, rapid-fire in delivery and brimming with absurdity, didn’t just entertain—it challenged cinematic norms. The nomination didn’t signal a career shift toward acclaim, but it cracked open a door. For once, laughter wasn’t just applause-worthy—it was award-worthy.

#20: The Eternal Legacy of The Stooges on the Walk of Fame

Decades after their deaths and the evolution of comedy, the Stooges remain beloved icons. 1983 their contribution was immortalized with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Despite their absence, the Stooges’ slapstick humor endures through endless remakes, re-releases, and animated series, ensuring their hilarious legacy lives forever.

#21: The Concept of ‘Fake Shemp’

The death of Shemp Howard birthed a cinematic workaround: the “Fake Shemp.” Using clever lighting, back-of-the-head stand-ins, and recycled footage, producers completed scenes without the man himself. This odd necessity gave rise to a filmmaking term still used today.

Whenever a stand-in fills in for an actor, they’re dubbed a Fake Shemp. What started as a quick fix to wrap up contracts became part of Hollywood’s creative lexicon. Shemp, unknowingly, left behind both a comedic legacy and a filmmaking technique. Even in death, he inspired innovation—proof that slapstick and cinema often overlap in the strangest ways.

#22: Television’s Resurgence of the Stooges

Television resurrected the Stooges when no one expected it. By 1959, their vintage shorts hit the small screen, sparking a new fanbase of children who had never seen a Stooge in theaters. Moe and Larry, long past their physical peaks, found themselves back in demand, though both had lost their brothers-in-comedy, Curly and Shemp.

The audience didn’t care. Syndication worked magic. Those old black-and-white reels, filled with pie fights and eye pokes, became after-school staples. The trio’s madness gained a second life in living rooms across America, proving that truly great comedy isn’t bound by time, only by airtime.

#23: The Evolution of Curly-Joe’s Look

Joe DeRita didn’t enter the Stooge scene with a shaved head. Initially, he resembled Shemp—full hair, softer edges. But the tides of television demanded a visual callback. So, with scissors and symbolism, he shed his locks and became “Curly-Joe.” The change was more than cosmetic—it was a calculated nod to nostalgia.

Producers wanted familiarity; audiences craved echoes of Curly Howard’s madness. Though DeRita lacked the spark of his predecessor, he embraced the image, clean dome and all. This visual reincarnation helped keep the act alive.

#24: The Late Career Shift into Travel and Comedy

Age has a way of taming even the wildest clowns. As the 1960s drew close, the Stooges, now silver-haired and slower-footed, recognized that eye-pokes and pratfalls came with physical cost. So they adapted.

With Kook’s Tour, they explored merging travelogue with comedy—part vacation, part performance. It was an ambitious pivot: showcasing America’s beauty while sprinkling in slapstick, tailored for an aging trio. Unfortunately, the project faltered due to Larry Fine’s stroke. Still, it marked their willingness to evolve.

#25: The Final Chapter of Larry Fine

In 1969, the music stopped for Larry Fine. A devastating stroke silenced his limbs and imprisoned him in a wheelchair. The dancer, the violinist, and the gentle middle Stooge were left to watch from the sidelines as his body betrayed him. Yet, even as his mobility faded, his spirit flickered—bright, stubborn, undeterred.

He remained gracious to fans, humorous with visitors, and reflective about a lifetime of laughter. The following years brought more strokes and mounting limitations. In January 1975, Larry passed away, not as a forgotten clown, but as a beloved figure whose humanity outshone even his most outrageous routines.

#26: Unveiling the Fourth Stooge

After Larry’s decline, Moe Howard refused to let the curtain fall. He introduced Emil Sitka—a longtime supporting actor within the Stooges’ universe—as the “Fourth Stooge.” Emil was cast as “Harry” in a retooled version of the act, symbolizing a last-ditch effort to revive the trio’s magic.

Plans were made, scripts drafted. But fate had other ideas. Larry’s health kept worsening, and Moe’s health began failing. Sitka never got his full Stooge debut. Still, the idea of a “Fourth Stooge” is one of comedy’s great what-ifs—a tantalizing fragment of a troupe determined never to say goodbye.

#27: A Final Bow

In 1974, Blazing Stewardesses was to be a comeback vehicle, a bizarre blend of bawdy humor and familiar faces. Moe, Curly-Joe, and the newly dubbed Stooge-in-waiting Emil Sitka were set to appear. But then, reality struck.

Moe was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer, forcing him to abandon the project and, with it, the final incarnation of the act. By 1975, both Moe and Larry were gone. The Stooges had defied decades, defied trends, and even defied death through editing—but not forever.

#28: ABC Elevates Three Stooges Saga

In 2000, ABC unspooled The Three Stooges, a made-for-TV biopic that dove beyond the eye pokes and pancake pratfalls. Audiences tuned in for nostalgia, but what they found was complexity—tales of backstage tensions, fragile egos, deep friendships, and quiet suffering.

Though the ratings were high, critics wavered. Some called it uneven, others too sanitized. Still, it gave the world a rare peek behind the curtain. The Stooges weren’t just clowns—they were craftsmen, survivors, and, at times, casualties of their success.

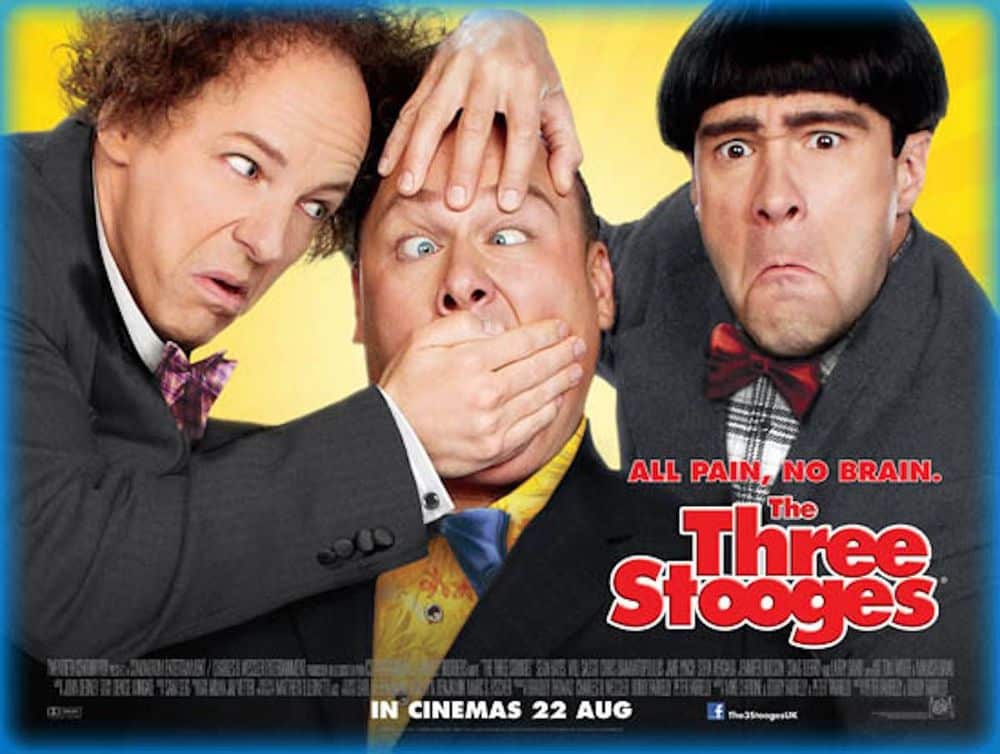

#29: The Three Stooges’ 2012 Cinema Revival

The Farrelly Brothers took a swing in 2012, resurrecting the Stooges not with a biopic, but with a stylized tribute that placed the trio—played by Chris Diamantopoulos, Sean Hayes, and Will Sasso—into three modern shorts. Critics were split. Was it homage or parody? Heartfelt or hollow?

Fans of the originals noted the precision—the voices, the timing, the chaos—but something intangible was missing. Maybe it was old Hollywood’s grit or the originals’ authenticity. The revival didn’t soar, but it sparked conversation. Trying to recreate the past reminded audiences why the real thing could never truly be duplicated.

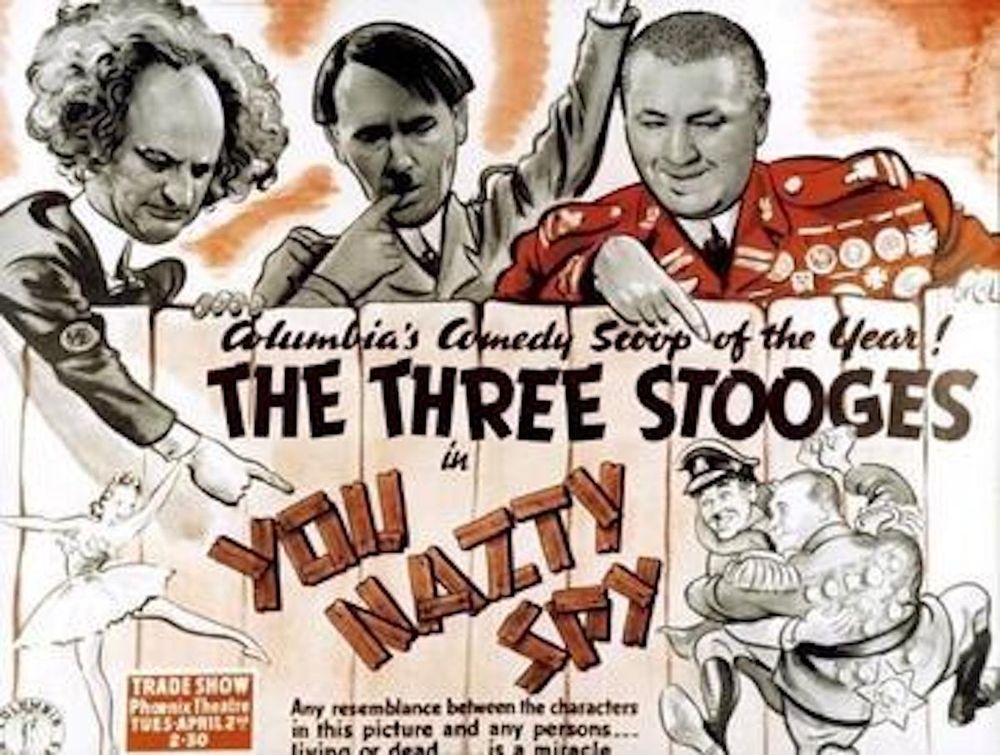

#30: Formidable Adversary

When the Stooges aimed Adolf Hitler in their 1940 satire You Nazty Spy!, they weren’t just poking fun—they were punching up, boldly. At a time when the U.S. had yet to enter World War II and many still tiptoed around the topic, Moe donned a tiny mustache and unleashed a whirlwind of ridicule.

Hitler reportedly placed the trio on his “death list,” labeling them “favored casualties.” Imagine that: three Jewish comedians, armed with custard pies and absurd accents, rattling history’s most infamous dictator. It was slapstick as protest, banana peels as resistance—a testament to comedy’s quiet courage.

#31: Larry’s Gambling Addiction

Behind Larry Fine’s perpetual daze lay a costly habit—gambling. He wasn’t just a weekend warrior at the racetrack; he gambled impulsively, often draining his earnings on horses and high-stakes games. Columbia’s weekly paychecks went fast, sometimes on a single bet.

Moe often had to step in to curb the chaos and keep the act financially afloat. Larry’s easygoing demeanor masked a man whose vices quietly nibbled away at his security. Despite fame and fortune, Larry died nearly penniless. His addiction was rarely mentioned publicly, but it was one of the fundamental reasons he was constantly teetering offscreen.

#32: Columbia’s Refusal to Promote Them

The Three Stooges were one of Columbia Pictures’ most profitable short-subject acts, but you’d never know it from their treatment. Harry Cohn, the studio’s president, refused to publicize them with posters or press. Why? He feared they’d demand better contracts if they knew their actual value.

So while their films filled theaters, they stayed in the shadows—underpaid, under-credited, overworked. They never headlined like A-listers because Cohn ensured they didn’t think like A-listers. It was manipulation disguised as modesty, and it worked.

#33: Curly’s Real Name Was Jerry

“Curly” wasn’t his real name, and even “Howard” wasn’t his birth name. Born Jerome Lester Horwitz, he was the youngest of the Howard brothers and never expected to become a star. His family called him “Babe.” He pursued ballroom dancing for much of his youth and flirted with opera singing.

The shaved head and silly voice came later, transforming him into a comic icon. But to those who knew him best, he was always Jerry—a soft-spoken, sensitive soul who just happened to find fame through frenzied footwork and falsetto yelps.

#34: They Slept in the Studio

The Stooges worked so relentlessly that, at times, they barely left the lot. During long filming stints, Moe and Larry occasionally sleep in their dressing rooms at Columbia Studios. It wasn’t glamorous—think cot, thin blanket, lukewarm coffee—but it kept them close to the action and on time for the next shoot.

Ever the disciplinarian, Moe believed in punctuality, even if it meant crashing near the soundstage. Their work ethic bordered on obsession. While others partied in Beverly Hills, the Stooges stayed behind, asleep beneath fluorescent lights, waiting for another day of banana peels and custard pies.

#35: Shemp’s Stage Fright

Shemp Howard was funny, no doubt, but crowds terrified him. Despite his years on stage and screen, he suffered from near-debilitating stage fright that never quite disappeared. Unlike his brothers, Shemp’s anxiety grew in live settings, where retakes weren’t an option.

His nervous tics became part of his comic character—eye rolls, shoulder shrugs, pacing. Audiences laughed, never realizing much of it came from genuine discomfort. It’s ironic: the man who ran from the stage’s glare still found himself, over and over, performing through palpitations.

#36: Moe’s Business Savvy

Moe Howard wasn’t just the ringleader on screen—he also ran the business behind the curtain. Unlike his brothers, Moe kept meticulous paychecks, contracts, and touring income records. He negotiated deals, reviewed expenses, and ensured the trio wasn’t financially ruined.

Moe urged the group to shift toward live performances when the short market dried up. While Curly cracked jokes and Larry floated through scenes, Moe balanced the books. His tough guy persona extended to the boardroom, where he slapped down bad deals and poked holes in studio excuses